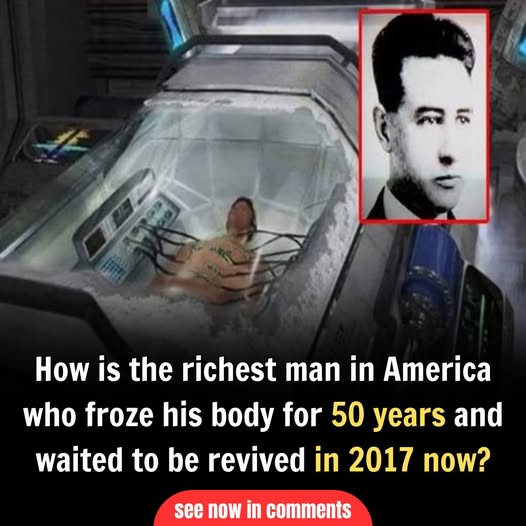

More than 50 years have passed, yet one question continues to intrigue scientists, researchers, and the public alike: Can modern science bring a cryogenically frozen person back to life? Has human technology advanced far enough to reverse death? Half a century ago, Dr. James Hiram Bedford dared to believe in that possibility. Driven by a strong will to live, Bedford volunteered to have his body frozen with the hope of being revived in 2017.

Now, more than three years past that milestone, curiosity remains. What happened to the man who made history as one of the first to undergo cryogenic preservation? James Hiram Bedford was more than just a man of science; he was an adventurer, a scholar, and a pioneer. A psychology professor at the University of California and a World War I veteran, Bedford lived an extraordinary life. He traveled the world, hunted in Africa, explored the Amazon rainforest, and visited countries like Greece, Türkiye, Spain, England, Scotland, Germany, and Switzerland. He even braved the Alcan Highway to explore the remote regions of northwest Canada and Alaska. Twice married and deeply passionate about exploration, Bedford left behind a legacy of curiosity and resilience.

In 1967, Bedford’s vibrant life was abruptly interrupted by a terminal diagnosis: kidney cancer that had metastasized to his lungs. At that time, medical science offered no cure. Faced with the inevitability of death, Bedford sought an unconventional solution inspired by Dr. Robert Ettinger’s groundbreaking book, The Prospect of Immortality. Ettinger, often referred to as the father of cryonics, had founded the Cryonics Institute to offer freezing services to preserve bodies in the hope of future revival.

On January 12, 1967, shortly after suffering cardiac arrest at the age of 73, Bedford’s preservation began. Under the supervision of Robert Nelson, one of the pioneers of cryonics, his body underwent an experimental process. Artificial respiration and cardiac massage were performed to maintain blood circulation. His blood was drained and replaced with dimethyl sulfoxide, a chemical meant to protect his organs from damage during freezing. Finally, his body was placed in a tank filled with liquid nitrogen, cooled to -196 degrees Celsius.

Bedford was not the first person to undergo cryogenic freezing, but he became the first to have his preservation maintained long-term. Months before him, in April 1966, a woman in Arizona was also frozen, but due to delays in the embalming process, cellular decomposition had already begun, rendering her preservation unsuccessful.

Before his death, Bedford allocated over $100,000 to fund the maintenance of his preserved body. Yet, despite his financial and scientific preparation, Bedford approached his preservation with a mix of hope and realism. His final words to Robert Nelson revealed his mindset: “I want you to understand that I did not do this with the thought that I would be revived. I did this in the hope that one day my descendants will benefit from this wonderful scientific solution.”

In 1991, after 24 years in cryogenic suspension, Alcor Life Extension Foundation technicians decided to examine Bedford’s preserved state. Cutting through the protective metal chamber, they found him wrapped in a pale blue sleeping bag, secured with nylon straps. His body was carefully transferred to a more advanced liquid nitrogen tank lined with polystyrene foam for improved preservation.

The examination revealed remarkable results. Bedford’s face appeared younger than his 73 years at the time of death. However, there were visible signs of decay: discoloration on his chest and neck, two small holes in his torso, and a faint smell of blood around his nose and mouth. His eyes were half-open, with corneas frozen into a chalky white state. His legs were partially exposed, with one crossed over the other. Cracks marred the surface of his skin, but overall, his preservation was considered remarkably successful given the technology available in 1967.

Once the examination was complete, the technicians carefully rewrapped Bedford in a fresh sleeping bag and returned him to his liquid nitrogen tank. Today, Bedford remains frozen in time, stacked vertically alongside 145 others who share a similar hope: that science will one day unlock the secret to reversing the effects of death.

Cryonics has come a long way since Bedford’s time, with advancements in cryoprotectants, freezing techniques, and cellular preservation. Yet the fundamental question remains: Can science truly bring a person back from a frozen state without causing irreversible damage?

For now, James Hiram Bedford remains suspended in liquid nitrogen—a symbol of human ambition and scientific curiosity. His legacy is not just a story of cryogenic preservation but a testament to humanity’s relentless pursuit of the impossible. Scientists and researchers continue to push the boundaries of technology, hoping to one day fulfill Bedford’s vision.

Whether or not Bedford will ever wake up is still unknown. But his story serves as a milestone in the history of cryonics and a reflection of our collective hope for a future where science conquers even death itself. Until then, Bedford remains frozen in time, a pioneer in humanity’s quest for immortality, waiting patiently for the day when science may finally turn hope into reality.